I had a zoom call with one of Britain’s most treasured artists, Mackenzie Thorpe, an artist so dedicated to his work that he’s worn his fingertips down so much (with his pastels) that he hardly has any fingerprints left!

Below is the transcript of the interview video, lightly edited for clarity, absolutely filled to the brim with Mackenzie’s stories, wisdom and rare explanations of his art techniques.

I hope you enjoy learning about Mackenzie Thorpe, one of my favorite great masters of our time. If you have a suggestion for another Great Master Artist for me to interview, write it in the comments below. I’d love to hear from you.

Mackenzie begins with a wonderful story about his first day in London as an art student…

I got a night bus down into London. I arrived at six o’clock in the morning, waited outside for the college to open. Then I stuck up a piece of board on the wall in my space that was allocated to me. I had a bag of paint and I started to paint. It wasn’t till 4:30 that afternoon that a woman called Kay Cox (this is 1979), and she said to me, Mackenzie, where are you staying tonight? I go ‘huh?’ I had nowhere to stay. I didn’t even think that far. All I wanted to do was paint pictures. And she said, ‘well, come and stay at my place’. (with Kay and her husband). That was the first time I had a glass of red wine and spaghetti bolognese.

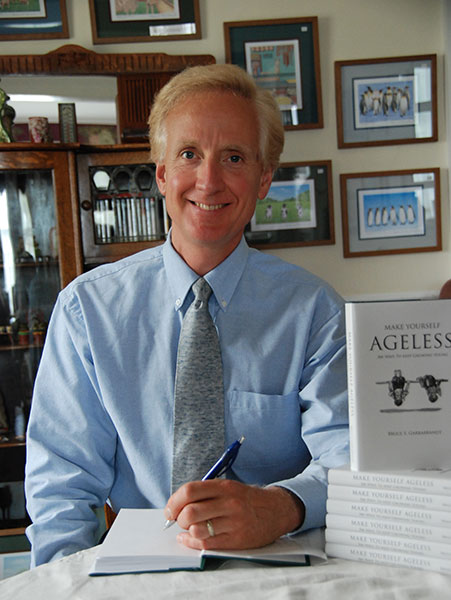

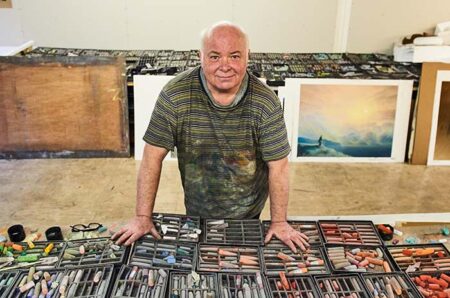

Mackenzie Thorpe in the studio with his pastels

Selling Square Sheep for 60 pounds

Cindy: When did you decide to make art your vocation?

Mackenzie: I thought, well, what if we opened an art shop selling materials? ’cause I’m fed up of going to an art shop and saying, ‘oh, have you got any Alazonian Crimson?’ And they go, ‘wha?’, you know… I want to go to an art shop where somebody can understand what I want and advise me. So I thought, well, I could do that. So we opened a small shop in Richmond, North Yorkshire, which has a big castle. It’s an ancient town with cobbled streets.

We were 57 seconds walk from the river surrounded by trees. And it was a fantastic place to be. But the business started to fail from day one because, yes, there’s a lot of artists in the area, but they might buy one tube of white paint and it will last them 12 months.

So I decided to use the materials and paint pictures of the area and sell them. That was the very beginning of it when I was selling pictures for five pounds. This is 1989. My business this year is 35 years old.

Then I start to draw my own interpretation of the landscape and my feelings; not trying to draw like a postcard photograph. And when that happened, people came in and asked ‘what’s going on?’

Then I did a piece that I priced at 60 pounds; these two sheep on a hill, and the square sheep. It was almost like having a Mark Rothko, but then putting the sheep’s head on the square with four feet on the landscape. And that was September, 1990. An American woman came in and she said, ‘oh my God!’ I said, ‘what, what, what, what?’ She said, ‘I was in a bar last night on the dales, and somebody said, ‘why do you Americans come here all the time?’ She said she replied, ‘because we don’t have walls like your walls. We don’t have fields like your fields. We don’t have this environment and that landscape and it’s beautiful and now for the first time I’ve found it in paint.’ ‘Wow’ she said. You are doing ‘what I feel about this area.’ And so she bought the 60 pound piece.

Then the radio heard about me. The press started to print about me, ‘the man that draws square sheep’. Now it’s successful. People queueing outside from all around the world to come buy this man’s work. And then it just went up, up, up, up… and you’ve got agents and galleries. ‘Can we show it? Can we have it? Can we do this?’

One day, two Americans just turned up at the space, the shop. The shop was only 17 feet by 12 feet, but with a window straight onto the street. So everybody watched me drawing and these two Americans came in and said, we think that you are the painter of hope and we want to represent you. As soon as one of them told me that he was Salvador Dali’s manager, I said, ‘whoa! That’s interesting.’

The Sheep and The Shepherd

Cindy: So Mackenzie, you’ve been telling us about the time when you created your most inspired work. So it was no longer about just the picture and creating the landscape and the picture before you, it was painting emotions and feelings. It’s like a language, isn’t it?

Mackenzie: Yes. I didn’t drop the motif. So I started to use symbolism. So one big sheep with two medium sized sheep and a small sheep. That’s my wife, my son and my daughter. And the landscape is where we were living. My job was to create and look at these things that we’re sharing and developing in our lives, and then put them in the pictures in a language that people would understand. So people coming to Yorkshire would see these sheep, then they’d find them in my gallery and say, ‘oh wow, look, there’s the kindness, there’s the happiness, there’s the softness’, et cetera, et cetera.

Or they’d see the shepherd going to work while they were asleep. He was out there lambing in the snow. He does it 365 days of the year he’s out there. I was invited by a shepherd to go and join him and do it. It changed a lot of my thinking about being a shepherd. We warmed our hands on the limbs of a lamb coming out of the mother. It was so cold. That’s why this man is so strict because he lives this life where things have got to go right, because things would be a danger if he didn’t fulfill his responsibilities. That also goes for the banker or a shipyard worker, my father, everybody’s father; he has to be strong, but he has to remember that with the stick he can help the sheep or with the stick he can harm the sheep.

I saw this as a village where the community is looked after and the village is the town, and the town is the city, and the city is the country. So when you walk home, no matter where you are, whatever language or nationality you are, and you walk into your house and the children are not smiling, it’s your problem. You’ve got to fix that.

So you’ve got these sheep going across the moors and the snow’s hitting them like this. And the shepherd’s going through it. And the sheep are all smiling because they’ve got no fear. They’re not frightened they’re gonna get cold or they’re not gonna get home tonight because Dad’s going to get us there. And we know he is gonna come home and look after us and do that.

I was telling somebody the other week, I was in New Orleans doing an exhibition, and every day we’re in restaurants and I said, as a child, we went to a restaurant once, once in all my childhood, I left home when I was 21. We went to a restaurant once. But we had everything that we needed. We didn’t have three or four pairs of trousers. We had one; that kind of thing. One pair of shoes. But we survived and we didn’t go to prison and we didn’t take drugs and we weren’t violent. And we all managed to grow up and have families and children. And I’ve got four grandchildren, you know, and my Mam and Dad didn’t have much, but they gave a hell of a lot.

‘So Much To Give’ by Mackenzie Thorpe

Mackenzie Thorpe’s Favourite Art Medium

Cindy: So let’s look towards the actual creation process of your art. Do you have a favorite medium?

Mackenzie: When I was working in the shop studio people could come in to buy greetings cards and things like that so I couldn’t use oil paint because of the smell. I couldn’t use acrylic because it sticks on everything and you can’t get it off. There were some pastels I was selling on the shelf and I used them. At college, the pastels were really bad. The quality was no good. I was selling good quality pastels.

Cindy: Do you remember the brand?

Mackenzie: Yeah, Rembrandt.

Cindy: Oh, Rembrandt. They’re beautiful, aren’t they? They’re so soft.

Mackenzie:That’s right. Yeah.

Cindy: Is that what you still use Mackenzie?

Mackenzie: No. What happened was, a rep came in and he said, have you heard of this brand called Unison? I said yes I have heard of it because around 81, 82 I was commissioned to show people how to use acrylic in a big hall in London. I was painting on the stage to show people how to use it. There was a man there making his own pastels, handmade pastels with pure pigment. As I got more successful, I could afford them, not just sell them, I could just take them. And that’s what I use.

Now, the one Rembrandt I still use is black intense noire, because black does not exist. It has to be made by humans. If black existed, all the lights in the universe would go out, then you’d have black. So I buy that intense noire and that’s my black. Everything else is done with these handmade pastels, Unison and their pure pigments. as old as this planet.

I like to work immediately. I don’t wanna sit around and say, ‘oh, shall I do this? Shall I do that?’ By the time I’ve done that, I forgot what I’m even drawing anyway. So I don’t want that time to think. It gets in the way.

Mackenzie Thorpe’s Favourite Paper

Cindy: What about the surface? Is that important?

Mackenzie: Ah, yes. Very. Yeah. I use Canson paper and it’s 50% recycled wood pulp, 50% recycled rag. There’s no acid in it. One side’s cold press, one side’s hot press. So one side’s got a tooth and one side is smooth as smooth. So I have an option. The pastels love grasping onto something. And the other one, when it’s smooth, it wants to fall off. So I press down my hands and you get a different texture.

Cindy: So the surface is really important to you. Did you seek long and hard to find that surface?

Mackenzie: No, but I’ve done things since, looking at different people’s pastels. Susan found this place in Paris who used to do Cezanne and Matisse’s pastels. I thought, wow. And they did gold and bronze and silver, which I’d never heard of. It was like women’s makeup. It’s so soft. But then when you put it in America, in the galleries, they don’t use glass. They use perspex for shipping because they go all around the world. And it’s such that there’s an electrostatic force that takes the pastel off. So I learned that. I had to stop using that.

Also, their reds would not mix with my reds. They stayed on the paper instead of being able to spread. So it’s perfect for doing this… (makes a rapid marking gesture). It kind of marks like that, but it’s not perfect for rubbing in. So I stick to the pastels that I know. The Canson paper is called Mi-Teintes conservation board.

My Gift For You by Mackenzie Thorpe

Pastels, Blood and Losing my Fingerprints

Cindy: But one thing I notice, Mackenzie, when you’re using your pastels, you use your whole hand, the palm of your hand. I always thought that the oils in your fingers would make the pastels repel. So how does that work? Do your oils stay on the page, the oils in your fingers? Tell me more about that.

Mackenzie: No, no, no. The only thing that gets in the way is blood. Using the rough surface. It doesn’t happen so much now because my fingers have got really thick, and I’ve lost most of my fingerprints, it’s very shiny. But in the early days, it would bleed quite quickly and the blood would turn black and you can’t get it out.

I get comments back, ‘what’s this mark?’

‘That’s my blood!’

‘We’ve got your blood in my picture?’

‘Oh yeah, that’s right. Yeah.’

I did a huge gouache painting once for a wine company. Years later he rang me and he said there’s kinda like, fungus growing on the picture. And I thought back and the paintbrush went like this (Mackenzie licks his paintbrush). It started to grow bacteria. When I told him that he was over the moon, he loved it.

Cindy: They have a little piece of you, don’t they. How special is that?

Mackenzie: That’s what they think.They make something out of it. So good. We’re all happy.

The Origins of Mackenzie Thorpe’s Big Head Series

Cindy: So I’ve got some other questions that I wanted to ask. One of the things that I’d love to know is the wonderful big head series that you draw. How did they first begin?

Mackenzie: I was frustrated. I’m dyslexic, and my son was having problems at school, and we found out that he is dyslexic. But the teachers didn’t want it, especially the headmaster. And they would more or less want to push it aside than look at it and help and support.

And I went one day, and I’m even sure it’s a Tuesday, I went and I got a piece of paper and I did that (Mackenzie makes big circular arm motion), and I put sort of one mark, 2, 3, 4 marks, that’s all it was.

And I thought, every child is born with a big head. Not one child is born sexist or homophobic, or, I don’t like green, I don’t like blue, I don’t like flying, or I don’t wanna do that. And the head gets smaller and smaller and smaller and smaller. When they get to 45, they wake up and say, ‘wha?’, what have you done in your life? Nothing. It just got smaller and smaller. And I thought people like Owen our child, he’s the same as all the children, were born the same. So was I. Why should they be pigeon holed so quickly by their peers, you know, or by their family. ‘Oh, don’t go play with him over there. He’s got green hair. You don’t wanna play with him.’ All these attitudes like that, instead of allowing their dreams to come true and hopes and try and discover things themselves.

That gave me the opportunity when a gallery would say, ‘the Big Heads, what’s this about?’ I would say what I’ve just said. And then I’d be invited to educational forums, dyslexia institution forums, where there’s mothers and fathers going through the same thing. Also educational psychologists. And I would do my talk about things like that.

I remember being in Japan at a forum about childhood. I was on the front cover of a national health magazine for 24 months. My work on the front cover each month was a big headed child, smiling. I put them all on a table in, in Japan, in this big forum, for the Minister of Education Dyslexia, or for people trying to raise awareness of dyslexic problems. I was doing that with a charity called Edge. I said, ‘what do you think of these?’ Eventually people start to talk about beautiful, innocent and happy. So I said, ‘why do we harm them? When are we gonna stop harming our children? The wars, starved nations. You can’t get a glass of water in Africa. What’s going on? And it made me be able to point these things out, and bring that conversation to the table. There was nothing for dyslexics in Japan. Now there’s satellites all across Japan.

I went to New Zealand to work with a guy there, called Guy. He wanted to do it in New Zealand. So we got it recognized by the government in New Zealand, Then he went on onto Australia. So by using that argument and people seeing the graphic, it made them think differently.

Cindy: It’s incredible the change that you’ve affected because of that one (circular) movement.

Mackenzie: When you think about it like that. Yes.

Cindy: You’ve just summarised the moment that it happened. What a privilege to hear that. Thank you.

Mackenzie: When you’re at conferences, and there’s people in the audience that have gone through so much because of the attitudes in the 1960s. These people see the work and see there’s hope. That’s what it’s about.

Blossom Grand (in situ) by Mackenzie Thorpe

It Doesn’t Turn Off. It Won’t Leave Me Alone.

Cindy: Do you ever go through times where you struggle? Like you procrastinate, where you can’t think of something to do or create, or if you do, how do you, how do you overcome that?

Mackenzie: It’s happening more as I’m getting older. Before I would just run at a piece and boom, be straight in there. but now, struggling a bit with my limbs and things, I’m getting older like that so I can’t do as much. And that upsets me a bit. That I’m not able to do what I want to do. But most of the time it doesn’t turn off, it won’t leave me alone. So when I go to work, I try to empty myself of everything. I don’t want anything inside my head. I don’t want to know what I’m going to draw.

I love to draw to music. My studio’s got, there’s maybe a thousand CDs, and now I’ve got Alexa. So I’ve got the world of music and what I try to do is use that as a soundtrack.

I’ve got a picture that I’ve started, but I don’t want to touch it until I’ve finished this interview. So I listened to Tommy Cooper to have a laugh. I want to bring some of that laughter into the work. How I’ll do it, I don’t know, but I want to. So there’s my start.

More and More Depth Than I’ve Ever Done Before

Mackenzie: I have responsibility, there’s 10 staff in the world of Mackenzie Thorpe. There’s galleries and agents so you can’t just take a day off or go on this because you want to. You’ve got to go to work like a plasterer or a bricklayer. But I’m fine with that because that’s how I was brought up. Go to work and Van Gogh said. If you can’t work, go to work. That’s my attitude basically. I try to do that. I go home earlier now because I can only do so much, but, what I’m doing is more and more in depth than I’ve ever done before.

Cindy: What do you mean by that? Can you elaborate on that more?

Mackenzie: If I was to draw a landscape 20 years ago, in a small space on the painting, I might get 20, 30 different clouds moving in. Now I’ll get 60, 120. It’s deeper and deeper and deeper. It’s not all about what you’re putting in, it’s what you’re taking out. I sometimes draw upside down to get the way I want the clouds to move. I don’t just draw the positive, I draw the negative to make this cloud move like that. Instead of putting the color on the cloud, I put the color on behind the cloud.

Matisse said, ‘you put your hand on the wall, draw the wall, and the hand will take care of itself.’ Monet said, ‘don’t draw the water. Draw what you see in the water, and the water will take care of itself.’

Now, I’ve just done a show in New Orleans, and that’s what it’s about, the reflections, making the picture and the solid; they’re not solid. They’re an illusion in a sense. You can put your hand right through it, but in a picture, they’re alive, they’re solid. I’m discovering all the time. I don’t stop discovering. I’m pushing myself.

Language When Words are not Enough

Cindy: It seems as though your work is continuing to evolve layers and layers as you grow and as you develop. You don’t just say that’s my style and I stick with it. You’re evolving with it. So it’s so much a part of you isn’t it? The way I look at it is, it’s like your language.

Mackenzie: It is a language. It’s my world. When words are not enough. My reason for being born and living on the planet is because pastel can’t walk across a studio and put itself on paper. I can’t draw without pastel and I can’t draw without that easel at the other side of the room. The three of us are all equal. We can’t work without each other. The tape, the music, my legs, my eyes, most of the body things I get rid of. I’m not aware. I don’t need to know that my heart’s beating. I’ve got legs and I’m not using them, but I just get into that space and I do it and I say, thank you very much for letting me go there today.

This morning, it was just a white piece of paper. Now look. Then you see it on someone’s wall and you go, huh! I remember the day when I drew that.

Cindy: That’s what it’s all about, isn’t it?

Mackenzie: Yeah, It’s not about all the other things that might come with it. If it might be for you, fine. You wanna draw flowers and you sold ’em for lots of money and you decorate lots of people’s houses, great. good for you.

Leaving Tees Port by Mackenzie Thorpe

Questions from Cindy’s Drawing Club

Cindy: We have had some audience questions for you. These are beautiful ladies from my drawing club. Would you like to have a listen to these and answer these for me?

Mackenzie: Yes I would, I’m very flattered. Thank you.

Spending Too Much Time on an Artwork

Cindy: So Dee Tracy, a wonderful member in our club has asked you ‘what is the most time consuming piece that you’ve created and how do you keep from feeling overwhelmed?’

Mackenzie: I’ll answer the second part first. I’m never not overwhelmed and I’ve got used to that’s how life is going to be. So stop arguing with it and just get on with it.

The first thing that came to mind was when you ask, it was this big six foot by maybe three and a half feet piece of paper. It was board, really, really thick, board. I was painting a winter scene with sheep over the dales, and I wanted to do snow and I hate spending time on one thing. So I put some dots on like this. And for the first time in my life I thought, well, it’s snowing all the way over there, and it’s snowing all the way over here. So these dots, they are this big. And the dots over there are (tiny)… three days…Oh no. I thought, ‘What have you done? You idiot! What did you do that for? What did you do? It’s crazy!’

After that, I was once with a group of artists, chatting at an exhibition, and one of them, Alan, he’s a fantastic photo realist animal painter, he had this painting in the exhibition of a tiger going into water. I’m not kidding you every single drop of water coming out the river had a reflection bouncing on another one.

I said, ‘how long did that take?’

‘Oh, about six months, seven months.’

And I said, ‘why didn’t you just go… duh, duh, duh!’ (quick painting motion)

He looked at me went, ‘ah!’

Mackenzie Thorpe’s Most Treasured Memory

Cindy: Now we’re going to move on to another question.

This is from Colleen Cook. When you think back to that time, do you have any treasured memories of when you first started to become an artist? When that lady bought that sheep, for example, because that was your first piece that you did in a stylized art form. Would you say that was the first time that you…

Mackenzie: Yes, It was.

My Dad said, ‘how are you doing?’

I said, ‘I think I’ve done something.’

And I rang up Tom, my old teacher and I said… well, at college they used to say, go and find out how Matisse did it. Go and find out how Rembrandt did it. Go to the library, do some research and come back. Then you might be able to get the idea how to draw it.

What do you do when you do a drawing and you go to the library and there’s no books on it? I said this to Tom and Tom says, that’s the job of an artist to try and communicate. So communicate with yourself first and then make it into a language that people will understand. It’s just another language.

Cindy: So that would be a treasured memory?

Mackenzie: No, the treasured memory is, something like… You finish the day’s work. You’ve had your photograph taken 20 times. You’ve sold work out in your little tiny space. It’s only two years, three years into the business and people are coming from all over the world to see you. And then you go home. And I remember I’d just go home and cry. Why? ‘Cause I didn’t know what to do with it. Like, who am I? It’s as Tom used to say, it’s only pastel on paper at the end of the day’. He said, ‘what people do with it, that’s theirs.’ I was in danger of taking what they are onto me, and that was the wrong thing to do. So I got confused.

Cindy: Can you tell me more about that?

Mackenzie: Then I met another guy, a very famous man who said ‘When I look in the mirror, I don’t go, whoa, look at that star’. He said, no, I just carry on shaving. Because you’re not changed.

I drew pictures all my life. My Mam didn’t pin one on the wall because she just saw drawings keeping me quiet. The school thought I could draw because I could do nothing else. I wasn’t celebrated for it. Now all these people are coming and spending good cash on my work saying I’m the best thing in the world, I’m this, I’m that. Can we have your photograph, can we do this? But I haven’t changed at all and I’m not going to change at all. I’m not gonna let it change me at all.

I suppose I was glad when this thing called success happened. I have two children, a great, fantastic, incredible wife, and this year is our 45th year of being married. If I hadn’t got that, then maybe I’d have went up the wall. So you might think your groundings are humble, but that humility can get you through the confusion and the glitter of the non-reality, and keep your feet on the ground.

You see my pictures with kids with big shoes on. Grandma said, ‘You’re at art college, but don’t get too big for your shoes.’

Mackenzie Thorpe

Mackenzie Thorpe’s Thoughts on Beginner Artists

Cindy: So it’s a great thing that you’ve had all that loving support. Now I’ve just got another question for you from one of my mentored students. Peta Turner is asking this question. She says, what is your best advice for beginning aspiring artists? It’s a question that many people ask. So I’m interested to see what your response is to that.

Mackenzie: Is there a beginning? Is there an end? Is there a middle? No. You’ve been an artist all your life. We all are. We’re all artists in different ways. Creativity goes right to the top bank manager, right to the guy (who fills holes in the ground).

There’s a hole in the ground. ‘Well, are we gonna sort this then?’ That figuring things out, that thing that makes you a human being. A camel doesn’t walk past a hole in the desert and think, oh, I think I should put some foundations in there to build a house.

Art is just a word, ‘A R T’ when you see it written.

Somebody said, ‘how do you draw love?’ What’s the answer? If I draw people kissing, that’s two people kissing. If I draw two people holding hands, that’s two people holding hands. How do you draw love? Everybody’s got their own interpretation.