Something unusual happens when I ask retired women why they want to learn to draw now.

They often apologize.

“I know I should have done this when I was younger,” they say. “I’ve wasted so much time. I’m probably too old now.”

But after teaching for 33 years, I’ve observed the opposite:

Retirement creates conditions for creative learning that simply don’t exist at any other life stage.

Not despite your age. Because of where you are right now.

Four Conditions That Change Everything

Retirement creates four simultaneous conditions that have never existed together in your life before.

Understanding these helps you see why now is actually optimal, not overdue.

1. Uninterrupted Time

What you had before: Fragmented time. Stolen hours. Moments squeezed between obligations. “Spare time” that was never really spare.

What you have now: Deep, uninterrupted blocks of time that you control completely.

This isn’t a luxury. It’s a requirement for skill development.

Learning to draw requires sustained focus—the kind where you can work for two hours without interruption, then return the next day and pick up exactly where you left off.

That kind of continuity accelerates learning exponentially.

When you’re not constantly context-switching between work demands, family needs, and personal development, your brain can build skills more efficiently.

The “starting over” every session disappears. Progress compounds.

2. Freedom from External Validation

What you had before: Everything you did needed to justify itself.

Your boss needed to see results. Your family needed you to be practical. Your community expected you to be responsible.

Every hour spent on yourself required defending.

What you have now: Freedom to pursue something simply because it interests you.

No justification needed. No ROI required. No one asking “but what’s the point?”

This psychological shift is profound.

When you’re not performing for approval, you can focus on genuine skill development instead of impressive-looking results.

You can spend a week on basic exercises without feeling guilty.

You can “waste time” (which isn’t waste at all) exploring techniques that fascinate you.

You can be a beginner without shame.

3. Decades of Visual Literacy

What you had at 25: Raw potential. Some technical facility. Limited life experience.

What you have at 65: Sixty-plus years of observing the world.

You’ve watched thousands of faces express emotion.

You’ve seen how light changes throughout the day across seasons and years.

You’ve observed body language in countless situations.

You’ve noticed how spaces feel—the weight of objects, the balance of rooms, the rhythm of compositions.

You’ve accumulated what artists call “visual library”—an enormous collection of observed information that your brain can reference.

Young artists have to build this library while also learning technique.

You already have it. You just need to learn how to access it consciously.

4. Cognitive Maturity

What you had at 25: Learning ability paired with impatience. Quick uptake but poor persistence. Easily frustrated by slow progress.

What you have at 65: Mature learning strategies. Realistic expectations. Hard-won patience.

You know from decades of experience that skills develop gradually.

You’re not expecting to be excellent immediately.

You’ve mastered difficult things before—professional skills, parenting, caregiving, complex projects.

You understand that frustration is temporary and progress is cumulative.

This cognitive maturity is worth more than the faster neural processing of youth.

The Convergence Effect

Here’s what makes retirement uniquely powerful:

It’s not just that you have these four conditions. It’s that you have all four simultaneously.

That’s never happened before.

In your 20s, you had processing speed and potential, but no time or freedom.

In your 30s and 40s, you had growing expertise, but crushing obligations.

In your 50s, you had skill and some flexibility, but still significant responsibilities.

Now, all four elements exist together:

Time + Freedom + Experience + Maturity = Optimal Learning Conditions

This convergence is rare. And it’s powerful.

What This Actually Looks Like

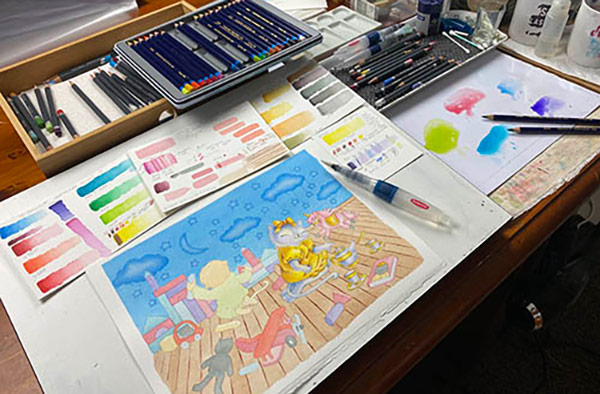

Let’s see an example. Sarah is 71 (not the lady in the image above.) Retired coordinator. Systematic thinker.

She works on drawing exercises for about an hour each morning, four or five days a week.

No interruptions. No guilt. No one needing anything from her.

She takes her time with each exercise. If something isn’t clear, she reviews the instruction again. If she needs a break, she takes it.

She’s not in a hurry.

After three months, she completed a self-portrait that stunned her.

“I couldn’t have done this at 30,” she told me. “I wouldn’t have had the patience. I would have rushed it, gotten frustrated, quit.”

“Now? I’m not proving anything to anyone. I can just learn.”

That freedom—to be a genuine beginner, to learn at your own pace, to focus purely on skill development—is the gift of this life stage.

Common Concerns About Starting Later

“My brain doesn’t learn as fast anymore.”

True, some types of processing slow slightly with age. But learning drawing doesn’t depend primarily on processing speed.

It depends on:

- Careful observation (you’re excellent at this)

- Pattern recognition (you’ve been doing this for decades)

- Systematic practice (you know how to build skills)

- Patience with the process (you have this in abundance)

These are all strengths that increase with age.

“My hands aren’t as steady.”

Drawing doesn’t require perfect hand steadiness. It requires accurate observation and comparisons.

Many of my most successful students have slight tremors or arthritis. They adapt their grip, take more breaks, work at their own pace.

The skill is in the seeing and thinking, not just the hand control.

“I don’t have years ahead to develop mastery.”

You don’t need decades. Significant skill development happens in just a few short months with consistent practice.

And who said the goal is “mastery?”

The goal is engagement. Growth. The satisfaction of developing a skill. The joy of creating something that didn’t exist before.

That happens immediately, not eventually.

The Research Supports This

Studies on adult learning consistently show that older learners often outperform younger ones in domains requiring:

- Sustained attention

- Strategic thinking

- Integration of complex information

- Realistic self-assessment

- Persistence through difficulty

These are precisely the skills that drawing requires.

Neuroplasticity—the brain’s ability to form new connections—continues throughout life. You can build new skills at 70 as effectively as at 30, just with different strengths supporting the process.

What Your Career Gave You

If you were a nurse, you spent decades:

- Making rapid visual assessments

- Noticing subtle changes

- Seeing patterns in complex information

- Working systematically under pressure

If you were a teacher, you spent years:

- Breaking complex skills into learnable steps

- Recognizing individual learning patterns

- Adjusting methods when something wasn’t working

- Persistent problem-solving

If you were a coordinator, you developed:

- Systems thinking

- Multi-variable analysis

- Attention to detail

- Long-term project management

Every single one of these skills transfers directly to learning drawing just in a different way.

Your career wasn’t time away from creative development. It was preparation for it.

Reframing “Late”

Here’s a different way to think about timing:

You’re not starting “late.”

You’re starting when you have, for the first time:

- Time to focus

- Freedom to explore

- Experience to call upon

- Maturity to persist

You’re not behind. You’re positioned.

The Question Isn’t “Is It Too Late?”

The question is: “Do I have the conditions for successful learning?”

And if you’re retired, the answer is almost certainly yes—more yes than at any previous point in your life.

You have time. You have freedom. You have accumulated visual literacy. You have cognitive maturity.

These four conditions create the foundation for rapid skill development.

Not despite your age. Because of where you are right now.

What Happens Next

Suzanna (not the woman in the photo above), the 68-year-old former teacher who thought she’d missed her chance?

She completed her first realistic self-portrait in twelve weeks.

Not because she was especially talented.

Because she had time, freedom, experience, and maturity working together.

“I couldn’t have done this at 28,” she said. “I would have been too impatient, too anxious, too distracted.”

“Now? This is exactly when I was meant to do this.”

That’s what I see consistently.

Not people who “should have started earlier.”

People who are starting exactly when the conditions are right.

Your Window Is Open

If you’re retired and wondering if it’s “too late” to learn drawing, consider this:

You have conditions for learning that you’ve never had before.

You have skills from your career that translate directly.

You have life experience that creates depth.

You have the patience and persistence that only comes with time.

You’re not too late. You’re precisely on time.

The question isn’t whether the window is still open.

The question is: Will you step through it?

What’s your experience been with learning new skills in retirement? Have you found advantages you didn’t expect? Share your thoughts in the comments.

About the Author

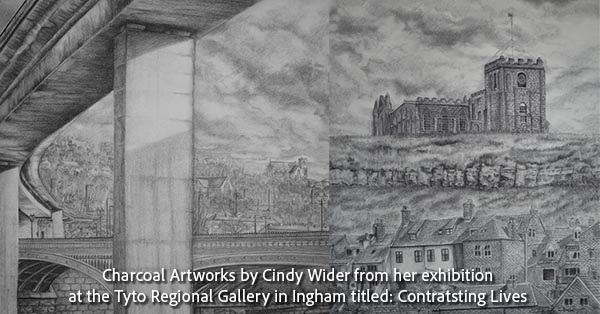

Cindy Wider has spent 33 years observing how analytical minds learn creative skills. Her work focuses on helping retired professionals recognize that their systematic thinking isn’t a barrier to creativity—it’s an advantage that becomes more powerful with age and experience.

Related Articles

Everything You’ve Been Told About Creativity and Analytical Minds Is Wrong

Related Articles and Extra Reading

Meet my clients and read about their journey

Examples of Before and After Client progression

You can Learn to Draw in 60 Seconds